There are so many weird and wonderful hobbies in the world of wildlife, and in the first few months of my traineeship I wanted to try everything. Joining the Trust immersed me in what felt like an exciting hub of ecological knowledge and practice, and it seemed that every day I'd come home with a new calling in life after being inspired by someone highly skilled in a niche field. Be it with birds, bats, bugs or butterflies, I took the advice of my colleagues and became a ‘sponge’ to it all, soaking up as much knowledge and experience as my brain could handle. While I have gained a lot of valuable hobbies from doing so, there is one particular interest that has really hit home. Luckily for me, it does not revolve around something that will fly away before you have time to focus your binoculars, or scurry into the undergrowth before you can discern exactly how many legs and wings and body segments it has. This thing will quietly and contently sit in one spot for weeks on end, taking in the sun and waiting for you to find it. I am talking of course, about the flower.

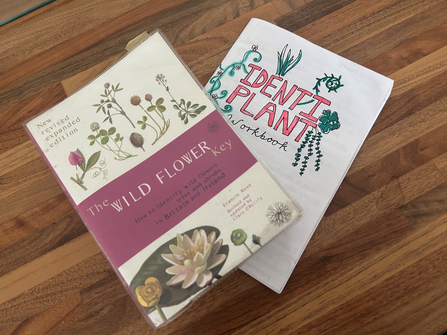

My interest in flowers started when I was enrolled on the Identiplant course as part of my traineeship. Identiplant is a programme that was adopted by the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland (BSBI) in 2022 and intends to introduce the key skills of botany to beginner botanists. The course comprises 15 units, the first three of which familiarise the learner with the correct botanical terminology and how to use an identification key. The following 12 units all centre around one plant family each and comprise an information sheet and a question sheet. For each of these units, you are tasked with finding and examining certain flowers that belong to the family in order to fill out the question sheet and complete the unit. Whilst this may sound daunting, you are supported throughout the course by your own personal Identiplant tutor, who conveniently happens to be an expert botanist in your local area.